The Diary

Someone finds the journal of a mentally disabled man in the archives This story was originally published on 4chan’s /lit/ board as part of a flash fiction collection that would later be released under the name “Simian Deluxe.” The story is semi-autobiographical and heavily based on the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute.

We are both wrapped up in our coats and our boots leave moist tracks across the tile floor as a radiator slowly clacks to itself somewhere in the distance. I keep close to her as we walk into the long hall of display cases, but can’t help falling behind as the scale of the space strikes us.

Countless votive figures stare out from behind glass. Silver snowlight pours through the windowpanes and lands against the soft glow of golden display lamps. Ancient kings stride across cylinder seal impressions rolled by long-dead curators. Heat and cold, motion and stillness come into contact around us, and for a moment we are smothered by the silent conflict of polar opposites. A mighty Lamassu turns its head to regard us with immobile judgment.

She works in the art collection, I work in the manuscript archives. We meet here after classes, in the hall of oriental antiquities, and I try to tell her how I feel. Afterwards we get coffee in the student union and I don’t see her again until the next week. This has been going on for a year. Today, I tell her about the diary I found in one of the high-density shelving units.

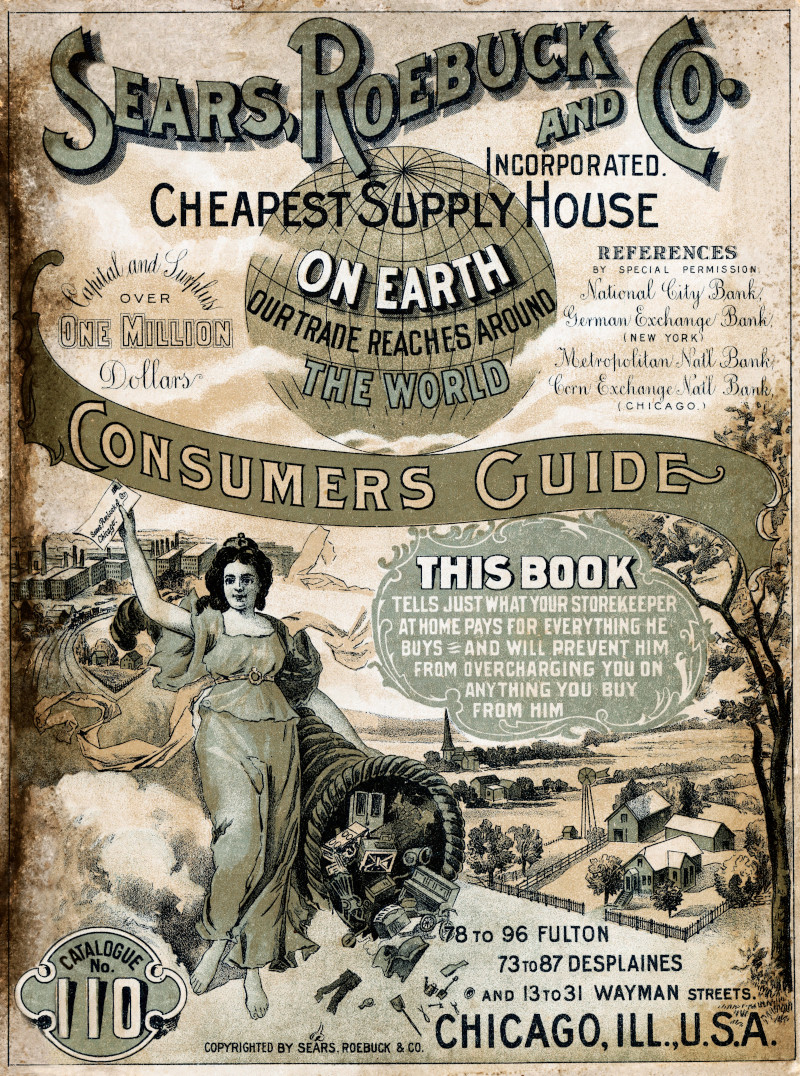

“At first, I thought it was just another old Sears catalog that had been misplaced. It was lying by itself on one of the shelves, no label or anything. When I picked it up, it was full of writing.”

“An inscription?” She gets it immediately.

“Yeah, someone had written all over the inside with what looked like charcoal. All big capital letters.”

“What did it say?”

“I don’t know. I could make out some names and dates, but the letters took up so much of the page that I couldn’t piece together entire sentences. I guess it was someone’s diary.”

“A man?”

I struggle to respond. An alabaster king uneasily shifts his weight against a supporting pillar.

“It was probably a man.” She answers her own question. “Someone who wanted to write but needed to rely on other people’s words.”

“It looked like it was written by a child.”

“A man-child, then.” She smiles and draws close enough that I can feel the slight pressure of her coatsleeve against mine.

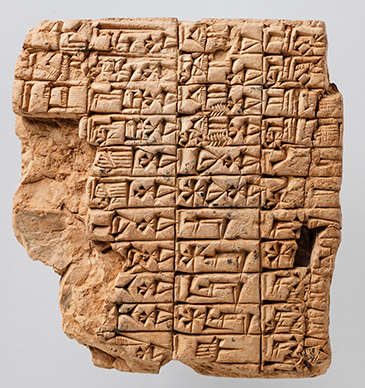

We have stopped in front of a clay tablet covered in tiny scratchmarks.

“Can you read this?”

I lean closer to get a good look. “She said to Enkidu: You are beautiful, Enkidu, you are become like a god. Why do you gallop around the wilderness with the wild beasts? Come, let me bring you into Uruk, to the residence of Anu and Ishtar, the place of he who is wise to perfection.” She actually seems a little surprised by this. Someone coughs from the other side of a bas-relief.

“I only know that part from class,” I confess. “My conversational Akkadian isn’t that good yet. I don’t think anyone’s is.”

She pulls away. “I wish you’d learn a real language, like French or German. Then you could help me catalog these paintings they have me working on.”

“But I don’t want to catalog paintings. I want to spend all day learning dead languages and reading books nobody can understand.”

She laughs at the joke, turns back, walks over to the case, and hugs me.

I don’t say anything else after that. As we walk to the exit, I regret lying to her about the diary.

It had been perfectly legible, once I took the trouble to write each massive sentence fragment down. The man who wrote it had a loose grasp on the English language and an obsession with trivial details. The few interactions with other people he recorded showed the signs of a severe learning disability. The time and place of his writing were unclear. The catalog was old, but it could have been old when he found it. He worked in some kind of general store, in the storage room where he wouldn’t bother the customers. His life was tedious and stupid, but he wrote it all down as if it were the most important thing in the world. Reading and writing were not easy for him, but he applied himself to both with an endless patience borne of limited horizons. His diary broke off in the middle of a sentence about shipping palettes. It was about a thousand pages long, more or less.

I transcribe it all and think of nothing else until I arrive at the gallery. When the time comes I lie to her about it, lie to the woman I love more than anyone else, lie as easily as a child telling his parents about stolen candy. She sees right through it, but doesn’t say anything. I realize this as I walk through the snow to my dorm. None of the statues say anything. They’ve been silent too long, and most of them never knew English to begin with.