Trying to Understand the Technocrats

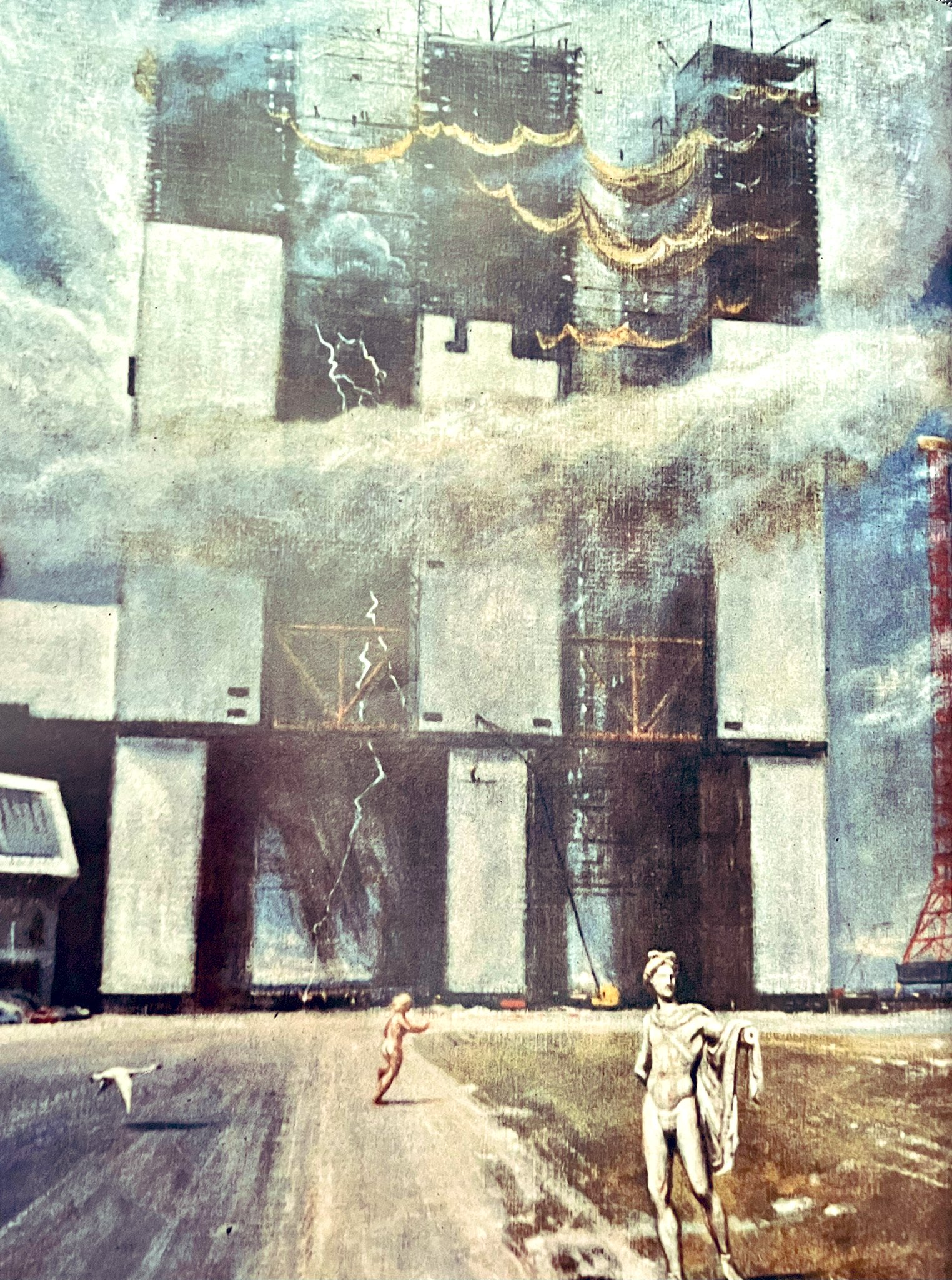

A brief response The image accompanying this post is a painting entitled “The New Olympus” by Alden Wicks, officially commissioned by NASA in 1964. The intended message is open to debate.

The following is something I originally wrote as a response to a post entitled The Rise of the Technocrats and the Fall of Labor Power, which was originally written by a Kiwi Farms user named “THASF” and later reposted on several other forums, including Agora Road. I’m only linking to the Agora repost (which wasn’t made by the original author) here because the original Kiwi Farms link is dead and I’m not confident that any of the site’s mirrors will stay up in the long term.

Technocracy is a subject I’ve been interested in for a while now, but the actual post that prompted me to write this is kind of a mess. I agree with the author’s point of view and think he’s half-right in many places, but he makes the mistake of reading the word “technocracy” as “non-democratic government by big tech capitalists” instead of using the actual definition of “non-democratic government by expert planners and social technicians.” Physical technologies like computers aren’t as relevant to technocracy as the sound of the word makes them out to be. Social technologies — methods of organization and planning, social engineering in the most literal sense of the word — are.

Strictly speaking, technocracy is not government by scientists and industrialists — it’s government run by organizational techniques (root word) borrowed (or so the technocrats claim) from science and industry. The most ambitious technocratic project ever attempted was the planned economy of the USSR. Other examples that come to mind are the Manhattan Project and the Apollo Program Many of the ideas in this post were lifted from …the Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age by Walter A. McDougall. (technocracy peaked in the 50s and 60s.) I can easily see the US devolving into a series of environmentally-justified five-year plans in the near future, but we aren’t quite there yet. I think there are some influential people who think it’s a good idea, but they face the challenge of overcoming their peers’ selfishness and converting them to The Plan. If we were actually being governed by technocrats right now we would all understand The Plan as clearly as a Soviet worker of the 50s understood his individual production quota.

The author also falls into the classic “conspiracy theorist” (scare quotes because it’s a loaded term) pitfall of defining his enemy by their actions instead of their intentions. You can’t win a fight against someone unless you’re willing to turn the chessboard around and see things from their perspective. With that in mind, I think everyone reading this should take a look at this article, which is probably the best example of a present-day argument for technocracy I’ve seen. (Fittingly enough I stumbled across it while researching Manhattan Project physicist Leo Szilard’s plan for world government.) Instead of imagining modern technocrats as deranged villains who want to maximize human misery, it’s more accurate to think of them as talented but spiritually short-sighted people who read that article and decide to apply its principles to solving a big social problem like climate change, income inequality, urban decay, etc.

Their ostensible goal will be to solve one of these problems, and to solve it they will create a Plan. They will remake as much of society as they can into a machine for fulfilling The Plan and they will do everything they can to ensure that as many people as possible see the fulfillment of The Plan as a good thing. You will live in a pod, eat bugs, and be happy, but not because your mind has been dulled or distracted. You will think about living in your pod and eating bugs in the same way that people in 1969 thought about Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin living in a pod on the Sea of Tranquility and eating freeze-dried food. It will be a grand adventure, the final frontier, solving one of the Big Problems of your age alongside the best brains your country has to offer. And you’ll love it. The experts will have succeeded in making your pod fairly comfortable and your bug food taste like a more nutritious version of a Chipotle burrito bowl. It might not be as nice as your old life, but you’ll put up with it because you’ll know that any sacrifices you make are in service to The Plan. You won’t love Big Brother. Big Brother won’t exist. You will love The Plan and you will see its success reflected in the smiling but slightly sickly faces of your friends and family.

I think a hypothetical technocratic success story like this is far more horrifying and illustrative of the evil of technocracy than the nightmare world described in the original post. The scary part is that there are a lot of ordinary people who would see the shiny, happy, planned world I’ve tried to describe as desirable. I think the appeal of technocracy comes from its roots in the Enlightenment idea that the world is essentially a machine. How do you save the world? Find the best technicians to run the machine for you. This idea of world-as-machine has been completely burned into the brain of everyone in the modern West, including myself. I often struggle with the idea that it might all be a Good Thing Actually. To reject it means either going back a couple hundred years or stepping outside Western culture entirely (the author I am responding to is correct when he says the Taliban are one of the few groups who can stand against the technocrats) and I would be lying if I pretended like either of those options sounded like a good idea.

I ended the original version of this post with an admission that I couldn’t offer anything resembling a solution, and stated that I would keep reading and writing about the subject in the hope of eventually discovering one. As of October 2023 I’m still in the same position, which isn’t that surprising since it’s only been a couple months. To be brutally honest, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to individually come up with a solution to the problems alluded to above, but I still think that talking and writing about it in a public place can do some good. This is the kind of thing the independent internet was made for, after all.